This May 15 marks the 13th anniversary of the singer’s last show: in Caracas and the approach of the ACV which was to make him enter an agony from which he never returned. The contours of his heritage are multiple. What was your relationship with your contemporary scene and why did the press always place you on a plane of footballing rivalry with certain peers? Here, a review of Cerati against the Argentinian rock that shouted from the canvas and the stage.

Gustavo Cerati was never a big football fan. And again, football has never shown Cerati too much respect either: fans have never embraced Soda Stereo as part of their creed of shouting, chanting and boarding, contrary to what has passed with other heroes of the Argentine songbook, such as Los Redonditos de Ricota, Bersuit Vergarabat, Los Auténticos Decadentes, Attack 77 or Fito Páez himself.

No great demonstrations of passion from the man of nothing personal towards some football greats of his country, beyond the cries in 1995, during a show in the city of La Plata, “¡Vamos Racing!”, was taken at the time as an obvious fanaticism for one Avellaneda clubs.

Of course, the musician did not escape from his most famous era to one of the phenomena that linked the guitars the most to the courts: the so-called “soccerization” of Argentine rock that moment when the press confronted the music greats as if it were a feverish Boca-River, while some of their fans behaved like real thugs, yelling at the singer of the opposing band.

In the mid 80s, or did you like it Sumo or Stereo Soda . Later, when Luca Prodán died in 1987, the position of the confrontation was taken by others: either you liked Los Redonditos de Ricota, or Soda Stereo. Specifically, either you identified with the philosophical mysticism of Indio Solari or the cool, edgy style of clothing of Cerati.

Read also: Biographer of Pink Floyd: “Roger Waters’ solo career was on the toilet, but as soon as he did The Wall, everything changed”

In the shows of Sumo or Redondos, chants wishing the “death” of Cerati were natural. As a counterpoint, at Soda concerts, the gunpowder was less lethal: it was simply rubbed away from a distance as they accumulated far more crowds and were more popular. “Olé olé, olé olé, it’s for the Indian who watches this on TV! It was the most common little song to show the ricotta mass its teeth.

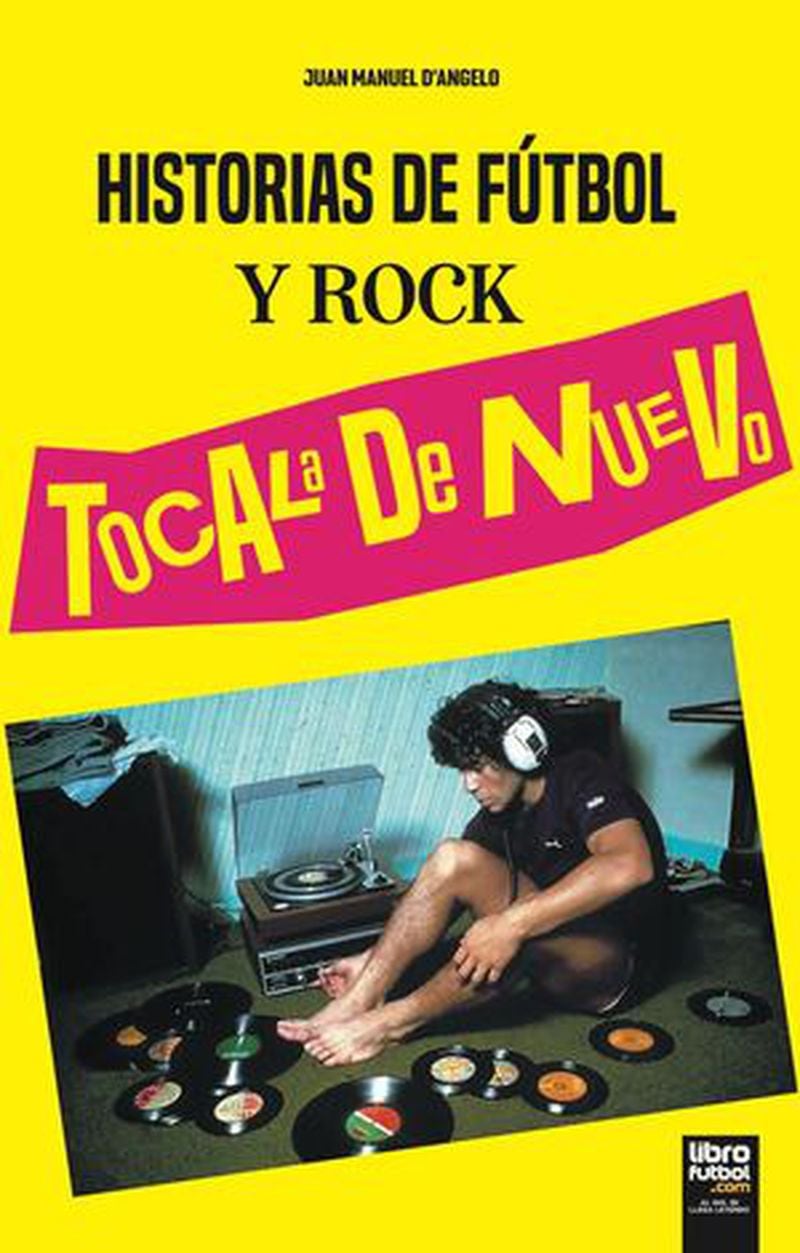

It also seemed to be a social and class problem . According to the book Football and rock stories: play it again, by journalist Juan Manuel D’angelo, the end of the Trans-Andean dictatorship in 1983 and the arrival of the democratic spring embodied by Raúl Alfonsín divided the music scene between those who believed that the hour of the party had arrived and the frivolous chaos who followed gray days –Soda Stereo, Virus, Los Twist-, and others who believed that rock should continue to be subordinated to a conscious, critical and frontal discourse –here they are from Sumo to Los Redondos-. Almost irreconcilable points. The most pop, festival and television mainstream that collides with the intellectual, anti-systemic and coherent underground.

The journalist Bruno Larocca illustrates it thus in the same text: “Audiences who followed Soda and Los Redondos sang against each other because they felt that their band’s progression was also theirs. For this public that started to follow them since they played in the first bars, coming to Obras was also a reward for themselves for always cashing in and following them since they played in nightclubs. no more than 30 people.

We’ve already said it: music fans have behaved like board haters.

***

Those involved have, on some occasions, added fuel to the fire. In 2016, Soda Stereo bassist Zeta Bosio spoke about the rivalry and, although he assured that “it grew more among the people”, his pulse did not tremble to comment on his supposed classic: “It seems to me that the la early Los Redondos music is not evolved, but rather basic rock.

Cerati has always been more measured . He felt that the supposed enmity between Soda and Los Redondos was a nest blown up by the media and that there was never any bitterness between them: “Soda versus Los Redondos or versus Sumo are the type of dichotomies that the Argentine needs to boot. Always with Sumo, because we came from the same place: us looking for the perfect song and them looking for the most imperfect song possible. But with Los Redondos, I don’t understand. I never understood that, while I was playing live, some were singing against El Indio. It’s true that in a song by Los Redondos the Indian talks about us climbing up the air. Maybe it annoyed him that we were singing La Cúpula, but I’ve always been a very scruffy guy and it’s also true that we were up there. We could talk about what was seen. It was never serious. The problem is that it has become political.

“Some nonsense even reads a rivalry between two Argentinians. I didn’t take it very seriously until I realized they were asking for my death. Because? Why is Luca dead and not me? As Luca said: Fuck you. If you sell that many records, not all of the people who buy them can be cheaters or strangers. Everything tires me. Geez, the reason I make music has nothing to do with being antagonistic to something or someone,” Cerati said in the mid-90s.

***

When the waters calmed down and the men became more adult, when Soda went on hiatus in 1997 and the Redondos were already consolidating as an unstoppable volcanic force, as their own cult insurmountable to any exogenous force, the panorama was different. . But not so much: the “soccerization” of Argentine rock began to diversify into bands that at one time seemed to be descendants of Indio Solari and raised an undisguised neighborhood, suburban pride and rock. All supported by hordes of fans immersed in the culture of “endurance”, this sidewalk existentialism where anything goes and where you have to support your favorite band through banners, flags, flares and whatever. I still.

A faith of blind and absolute abandonment. A dynamic where the audience is as much a protagonist as those on stage. La Renga, Jovenes Pordioseros, Los Piojos or Los Gardelitos, among many others, have entered this box once.

Read also: Madness for Indio Solari: Hell is charming

The most dramatic peak of this demonstration occurred on December 30, 2004, when a flare during a recital by the group Callejeros – icons of the neighborhood rock movement – caused a fire in the República de Cromañón establishment, which left 194 years – old tragedy. dead. “The media was quick to point out that rock music football was the main culprit,” the book says. Football and rock stories.

Cerati, as a relevant player in his country’s musical circuit, did not stay away from the discussion. Although he is not linked to almost any of the tops of “neighborhood rock”, the media has consulted his opinion and thoughts in interviews. There was even a detail: in 2003, in full bloom of rock with football accents, the walls of certain districts of the city of Buenos Aires woke up with an insulting scratch against Cerati: “Old kid”.

A few days later, another graffiti appeared with the same poison, but reversing its legendary farewell phrase “Thank you, total!” : this time it read “Total double chin!”. For the media of his country, the reading was this: for many, the author of American Blind had imposed himself in his solo era as the incarnation of a stagnant, bourgeois and wealthy creator, and who had little to tell the new generations that they drank from another stick.

Perhaps as a consequence of all this, the musician was one of those who raised their voices the most to criticize the “soccerization” of which the scene of his country was already a victim. “We’ve been playing with these levels of unconsciousness for many years. Getting people to carry flares or three shots is a really big asshole. These things became the symbol of rock and that’s because the public also wanted to be the protagonist. I consider it a mistake that the audience sometimes adopts such a strong participatory attitude, because at some point you end up feeling like the audience is the show. I never really liked it,” he says in the book. Rock and football stories.

In an interview published in the book Cerati: intimate conversationsby Gustavo Bobe, also threw darts at neighborhood rock: “I think it’s also a business and that those who say it’s not a business and they do it out of love for the neighborhood , lie to people… Talking about love for the neighborhood is real business and that’s why they do it! I say: you play in a shitty place, all bad, where there is no people suck like crazy, you put two mangoes on the glass, you sell a lot and here we go and here we go… It’s the crazy truth! Take off your mask!”

Then he continued: “So it’s not that I object, but I remain someone opposed to this hypocrisy because I say what I think. And best of all, there are a lot of people who think like me. I’m not against neighborhood rock or anything. For example… I’m tired of being asked questions about Los Redonditos de Ricota! I never had one and I never will. In addition, they asked me a football question when in reality, I don’t even like football”.

With this sentence, Gustavo Cerati seemed to close this circle which had imprisoned him since its origins in a footballing face-to-face that he never sought too much.

On the contrary, after his death on September 4, 2014, his supposed greatest antagonist, Indio Solari, seemed to make peace and end the confrontation forever. Boca-River could continue. They don’t.

“Gustavo, now you can avoid the fatigue of running away from death” Solari’s message began in a letter he wrote on his blog that day.

Read also: Gustavo Cerati: how was the last concert that triggered the drama

“All this sleep time was necessary, perhaps, to teach you how to die consoling your loved ones. True artists, I am convinced, know death before they die. They don’t get carried away a minute before or a minute after coming to terms with life. It is said that at death we are given the secret of music in our first birth cry”.

“As for what I get, you gave me the benefit of your sweet voice and your splendid playing with the guitars. Your solo scene was solid and adventurous and that’s what I like the most about what you left us”.

Continue reading in Cult:

Source: Latercera

I am David Jack and I have been working in the news industry for over 10 years. As an experienced journalist, I specialize in covering sports news with a focus on golf. My articles have been published by some of the most respected publications in the world including The New York Times and Sports Illustrated.