It was in Mendoza, on April 8, 1818, when Juan José and Luis Carrera were shot. They had been caught trying to return to Chile to carry out a coup against the O’Higgins government. Here, we tell the ins and outs of one of the least known events in our history.

Death is always difficult to write. This strains the wrists and makes it easier to resort to platitudes. But the pulse of Toribio Luzurriaga , governor of the Province of Cuyo in Argentina, the year 1818, was rather calm. With neat handwriting – as evidenced by the document kept in the National Archives – he wrote:

“While justice exercises its own without any restriction. You know that D. Juan José and D. Luis Carrera tried to carry out a plot against the public peace and constituted authorities on February 29, with the double objective of overthrowing the order in the united provinces, of invade the State of Chile, ignite the fire of civil war, and divide the attention of the united state with imminent danger to the freedom of both countries…”.

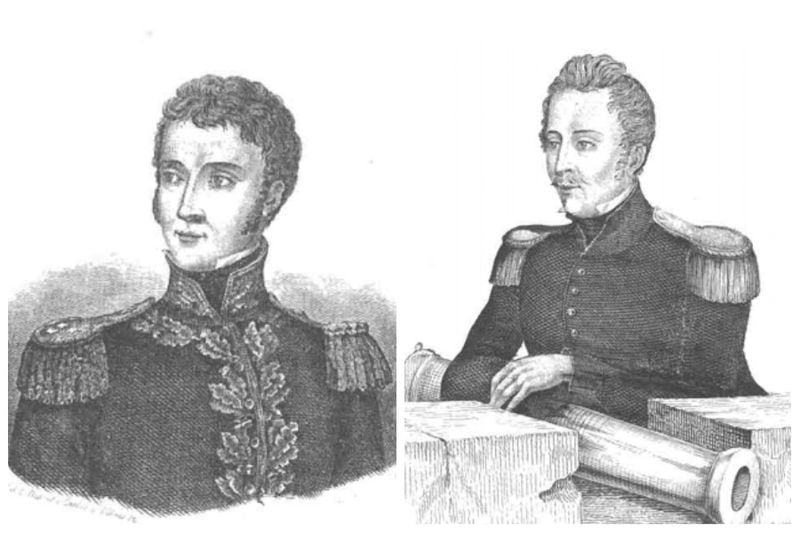

It so happened that the Carrera brothers, who had exiled themselves from Chile after the disaster of Rancagua (1814), had been removed from the distribution of power at the same time as the governor of Cuyo, Jose de San Martin , took part for Bernardo O’Higgins and not for Jose Miguel Carrera , who demanded that San Martín be recognized as the supreme government of Chile by virtue of being the commander-in-chief and main political leader at the time of the defeat.

However, San Martín ignored him, why? Argentinian historian Beatriz Bragoni explains it to Worship. “The Governor Intendant categorically rejected his request for two main reasons: the belief or the idea that the said recognition implied the erection of a State or a government within the jurisdiction of Cuyo and the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, and the confidence placed in O’Higgins mediated the opinion of friends of the lodge who, in London, had sworn to fight for the independence of Spanish America.

In this context, it is understood that Juan José and Luis Carrera were in Argentina in 1818. In fact, Luis had assassinated Colonel Juan Mackenna, a man close to O’Higgins, in a duel. Seeing themselves far from power, and with José Miguel in Montevideo (after being released from a prison in Buenos Aires after the confiscation of a fleet he had obtained in the United States), they decide to act.

The idea -in the middle of 1817, after the victory of the patriots in Chacabuco- was to return to Chile, to make a coup and to regain power. The plan included taking San Martín and O’Higgins “by surprise”, keeping them in separate confinements and forcing them to sign executive orders handing over the Carreras to the government and military. If that failed, the plan would turn into a war of montoneras and guerrillas who, they believed, would take over the country within months. All attractive for supporters who still thought they had in Chile.

A robbery that gave it all

For security reasons, and in order not to attract attention, they decided not to go to Chile together. Luis left first, in mid-1817, using fake passports and unusual clothes for him. He was accompanied by a friend, a man from Chillanejo named Juan Felipe Cárdenas. But in Mendoza, when there was not much left to cross the mountain range, the shadow of bad luck took hold of him. He was recognized by a former Chilean army officer, José Ignacio Fermondois, who – apparently by Diego Barros Arana – reported the young man to the provincial authorities.

Arrested, he said he had no intention of going to Chile to lead a revolt, but simply to return to settle in the country, due to the economic difficulties he was going through in Buenos Aires. The papers and luggage they were carrying did not contradict their version. However, one detail ended up revealing everything.

Clumsily, on the way to San Juan, Luis Carrera had stolen the postman’s correspondence from La Rioja. I thought I would find something about him, but I didn’t. News of the robbery reached the authorities in Mendoza, who questioned Cárdenas, and he – under the offer that he would be saved from the death penalty if he cooperated and seeing that his friend had been arrested – ended up all confess: from the Carrera conspiracy to the theft of mail.

Moreover, seized with nervousness and fear, Cárdenas committed the folly of telling his captors that Juan José Carrera was already on his way under a false name through the province of San Luis. This alerted the authorities, who ordered his capture and promptly informed San Martín, who was in Chile. He informed O’Higgins, whose reaction is known by a letter.

“nothing surprises me [sic] what V. tells me about the Carreras. They have always been the same and will only vary with death. Until they receive it, the country will fluctuate in incessant convulsions,” reads the letter quoted by Diego Barros Arana in his classic General History of Chile.

Juan José was imprisoned in Mendoza, they were waiting for him thanks to information provided by Cárdenas. He was taken to San Luis, and there he did not hesitate to confess everything. Later, he was chained and taken to Mendoza, where he was placed in a different cell from Luis. It was September 1817.

But they made another mistake. In February 1818, and with the help of one of the guards – named Manuel Solís – the two brothers planned to enlist the support of the rest of the guards and revolt from prison. The idea was a little feverish. “They were convinced that Governor Luzuriaga was hated by the people; that it was easy to depose him, withdraw his command, seize the arms of the place, form a body of troops with the volunteers who wanted to help them, and with the royalist prisoners who were in Mendoza, to penetrate immediately into Chile Barros points out. The plan was Luis’s and Juan José reluctantly accepted it without being convinced.

They would do this all night from February 25 to 26 (not the 29th as noted by Luzurriaga). But, like a tragic fate that followed them to the end, the Carreras’ support, Solís, made the mistake of telling his friend the whole plan, and he went to see the governor, who foiled the whole attempt. Then they went to trial, which was accelerated due to the defeat of the patriots at Cancha Rayada (March 19, 1818). Faced with fear, many Chilean patriots returned to exile in Mendoza, and the news reached that far. However, since it was not a fatal defeat, the chances of victory were latent, and it happened precisely in Maipú, with an embrace of O’Higgins in San Martín included.

Last hours

Despite the victory of the patriots in Maipú, the fate of the Carrera family was cast. On April 8, they were sentenced to death and the sentence was to be carried out at 5 p.m. the same day. They were notified in prison at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Only two hours before being shot. “Tradition says that Don Luis Carrera listened to his sentence with noble integrity, and that his brother Juan José, sad and dejected, burst into imprecations to demonstrate his innocence and the inhuman injustice of which he was the victim,” Barros said. .

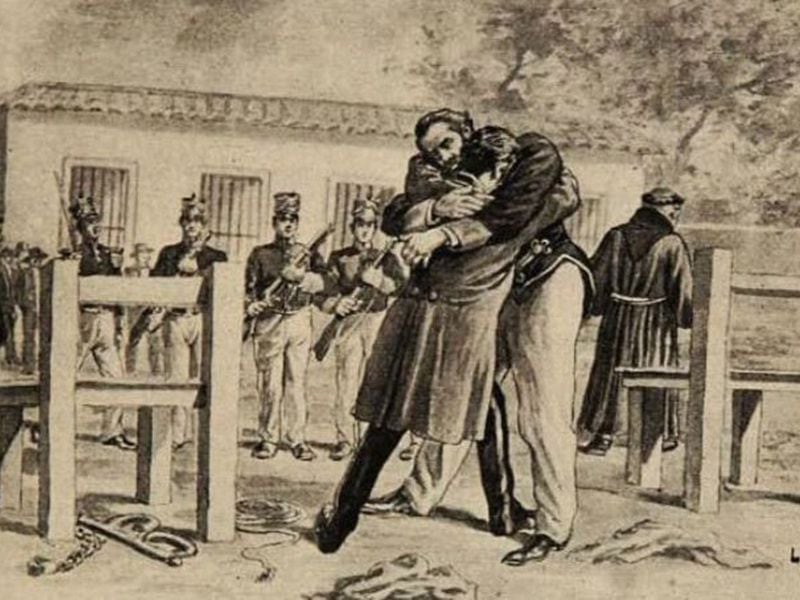

Both were spiritually assisted by Fray Benito Lamas -who three years later would do the same with José Miguel-. At 4 years old, they write a few writings where they leave their last wishes in wills, in family and patrimonial matters. Trying, hastily, in the Plaza de Mendoza (now Plaza Pedro del Castillo) two dirty benches were set up for the convicts, placed against one of the walls of the city jail.

The preparations took longer than they should have, and finally the execution was postponed for an hour. Around 6 the two brothers – who had already been placed in the same cell for a few months – were taken to the square. “They were dressed in their best clothes, leg irons, and they paraded slowly in the middle of a sepulchral silence and in front of tight groups of spectators”, says Barros Arana.

“Witnesses to this painful scene recounted that Don Luis then showed remarkable serenity, while his brother, although visibly dejected, never ceased to protest his innocence and to deplore the iniquity of his sentence.”

At 6 a.m., both seated on the pews, the sentence was read to them, then a shotgun blast cost the two brothers their lives. Juan José was 35 and Luis 26.

Continue reading in Worship

Source: Latercera

I am Robert Harris and I specialize in news media. My experience has been focused on sports journalism, particularly within the Rugby sector. I have written for various news websites in the past and currently work as an author for Athletistic, covering all things related to Rugby news.