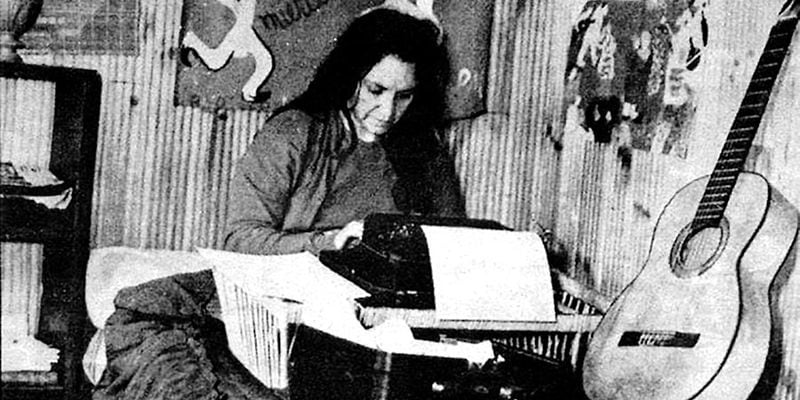

Isabel Parra was not with her mother when she committed suicide on February 5, 1967. She found out almost by chance a day later while going to buy milk. This is what the recent and remarkable documentary En September canta el gallo reveals, dedicated to Chilean music of the 60s and 70s.

This was not the first time that Violeta Parra had attempted to end her life. In fact, that summer of 1967, he frequently oscillated between anguish and torment.

“In one he used barbiturates and in another he cut his wrists. Difficult to save, she later said it was the result of accidents; However, he insisted on his intention to eliminate himself,” he dramatically detailed at the time. The third.

In January 1967, a month before the fatal outcome, the Uruguayan musician Alberto Zapicán – her last partner and who lived with her at the time – found her in her room in La Carpa de La Reina lying face down, thrown on a bed . with self-inflicted cuts on his arms. In fact, he had to destroy the door with blows to be able to enter.

There, when he saw the scene, he took a pair of bandages and tied a few knots to contain the blood and wounds. He had saved his life.

But on Sunday February 5 of the same year, everything was different. Violeta Parra would get up in the morning to have breakfast, drink tea and then lock herself in her room. No one dared to speak to him. Zapicán himself and his youngest daughter, Carmen Luisa Arce Parra, were also present in the tent.

The author had been struck for months by the end of her relationship with the Swiss anthropologist Gilbert Favre left for Bolivia, burying the most transcendent sentimental link of his existence.

In the morning, isolated from the world, Violeta listened Manzanares River, a Venezuelan song recorded by Ángel and Isabel. ““My mother is the only star / that lights my future / and if she dies / I will go to heaven with her” says part of the letter.

After lunch, he returned to isolation. This time he wrote non-stop. He drank some wine and around five in the afternoon he left his room. He chastised Zapicán for all the problems between them: discussions were constant with the Uruguayan and that day there was no sort of white flag. After that, he returned to his room, took the Brazilian revolver he kept in a drawer and shot himself in the right temple. It was a quarter to six. He was 49 years old.

“The body of the artist, founder of an internationally renowned group, was discovered by her partner, the Uruguayan singer Alberto Jiménez Andrade. [el nombre real de Zapicán] and her 12-year-old granddaughter, Carmen Luisa,” La Tercera reported.

Zapicán had to break down the door once more, but the situation was now desperate. The country’s biggest emerging artist was gone forever.

From a certain distance

Her eldest daughter, Isabel, was not with her. Because it was summer time, I spent the summer in Horcón. For the rest, I had stopped living with the author of Thanks to life.

“The day my mother…that Sunday. I was on vacation, on a Sunday, with friends. I remember I didn’t have lunch. They were talking, I start to feel bad and the night comes and I ask Tito (editor’s note: singer-songwriter Tito Rojas) that we leave,” says Isabel Parra in the remarkable documentary In September the rooster crowsby Nano Stern and Luis Briceño, premiered last week at the Nescafé de las Artes theater and addresses the feverish period of local music between the 60s and 70s, with a particular emphasis on new Chilean song.

Then he continues: “On Monday, I’m going to get the milk that Mrs. Carmen sold us. And I came up to her and she had a face that I won’t even tell you about.

“‘I’m coming to get the milk, Mrs. Carmen’ (I tell her). And she says to me: ‘Don’t you know what happened to your mother?'”

In the recording, Isabel Parra becomes emotional and opens her hands, a clear sign that she wants to stop the story at that moment.

On Monday February 6, 1967, the artist was detained in her same tent in La Reina. The press of the time claimed that the first floral offering came from Gabriela Pizarro, a folklorist who led the group Millaray, trained alongside Violeta. The mayor of La Reina, Fernando Castillo Velasco, also offered his condolences. The children, Ángel and Isabel, arrived precisely from the central coast.

The Third was present on the scene. “In a corner, among a pile of chairs, a harp. On stage, between the crowns, a yoke. From early morning, people began to march. Before leaving for work, the neighbors. Around noon, the people who admired her and who often listened to her songs while she ate an empanada and drank a glass of wine, under this same tent, which was the folklorist’s residence in the last years of her life and which received it now, in death. In the afternoon, the artists, friends of her or her children, who, with bowed heads, receive condolences.

Violeta Parra was buried at the General Cemetery on Tuesday February 7. The coffin left the Queen’s tent at eleven o’clock in the morning. A crowd of people and a long caravan of vehicles followed the procession. There was even a tribute from the pergoleras.

“A long and sad call for silence silenced the sobs of those close to Violeta Parra and increased the consternation on the serious faces of her friends and admirers,” details the chronicle of La Tercera. The coffin containing the remains of the extraordinary folklorist was gradually lost, swallowed up by the black mouth of a niche in gallery 31 of the General Cemetery.

Continue reading in worship:

Source: Latercera

I am Robert Harris and I specialize in news media. My experience has been focused on sports journalism, particularly within the Rugby sector. I have written for various news websites in the past and currently work as an author for Athletistic, covering all things related to Rugby news.