Between September and November 1880, a Chilean force under Patricio Lynch traveled to northern Peru, determined to inflict economic damage on the nation with which it was at war. For various reasons, the government in Lima was unable to come to the aid of the region, and it is still today an episode that arouses controversy in the historiography. In Culto we review it with the help of a Chilean and Peruvian historian.

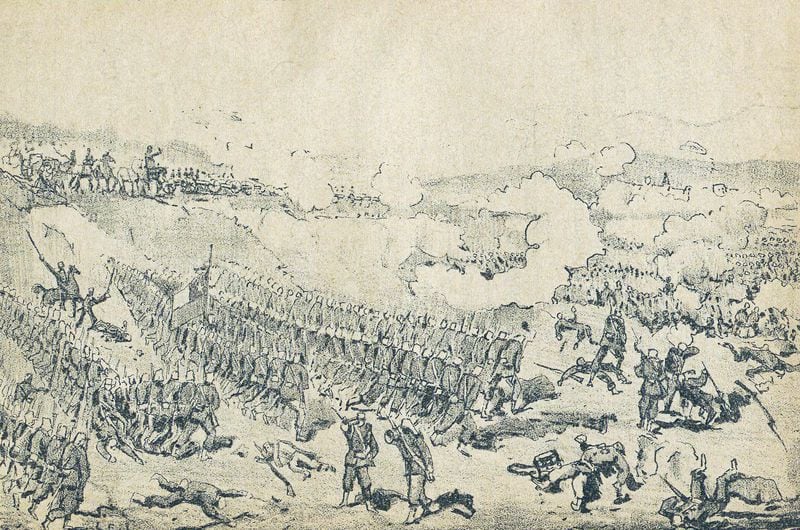

Towards the last months of 1880, the Pacific War had entered a decisive phase. After the Chilean victory in Battle on Alliance Field next to Tacna, Chile was preparing to prepare the next, perhaps decisive, blow that would allow it to end the war actions and retake the previously conquered Peruvian territories.

That’s when an idea was born. A military expedition that went to Peru determined to destroy the enemy nation’s economy. This was common in conflicts, as explained Worship the historian Rafael Mellafé. “In second generation wars like the Pacific War and calls for attrition or attrition, one of the goals is to destroy the enemy’s industrial and economic capacity so that they cannot cover the expenses of the war and does not have an industry capable of sustaining it. In other words, drowning them economically. There are several contemporary examples, notably the “scorched earth” tactics of General Sherman during the American Civil War.”

Thus began the study of an area to which the expedition was to be limited. After reviewing maps and plans, Chilean leaders decided to focus on northern Peru. “The goal was to tax wealthy landowners in northern Peru with money or spices. -Mellafe emphasizes-. This, make them feel that the war was not limited only to southern Peru but could encompass the entire territory; reduce or end the financial support that these businessmen provided to President Piérola and thus cause significant economic damage.

The area where Piura, Lambayeque, La Libertad and Ancash are located is the most productive agricultural region in Peru. . An essentially rich region. “In this region were located the most important sugar and cotton producers in Peru. -adds Mellafe-. In fact, the so-called “Ingenio de Palo Seco”, a sugar producer and owned by Dionisio Darteano (one of Peru’s “notables”), had an investment of one million pounds sterling, a huge sum for the ‘era. »

The Peruvian historian Daniel Parodi Revoredo, professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, adds: “At that time, sugar and cotton were massively cultivated. . These were large, modern agro-industrial farms that produced for export. There were even railways that transported production directly to the port for shipment, as is the case from Pimentel to Lambayeque.

Indeed, Parodi emphasizes that the region was going through a period of industrial development and that the economic situation was not optimal. “These haciendas were also just being upgraded with modern machinery to increase production due to the guano boom. In the context of the Pacific War, it was the only area of the coast, rich in resources, that Chile had not conquered militarily, since the Saltpeter and Guano Islands were already under the control of the invader. . However, we must not forget that in general Peru was bankrupt since 1872, that the great global depression of 1873 aggravated this situation and even more so the war, with which the economic crisis affected all sectors of society .

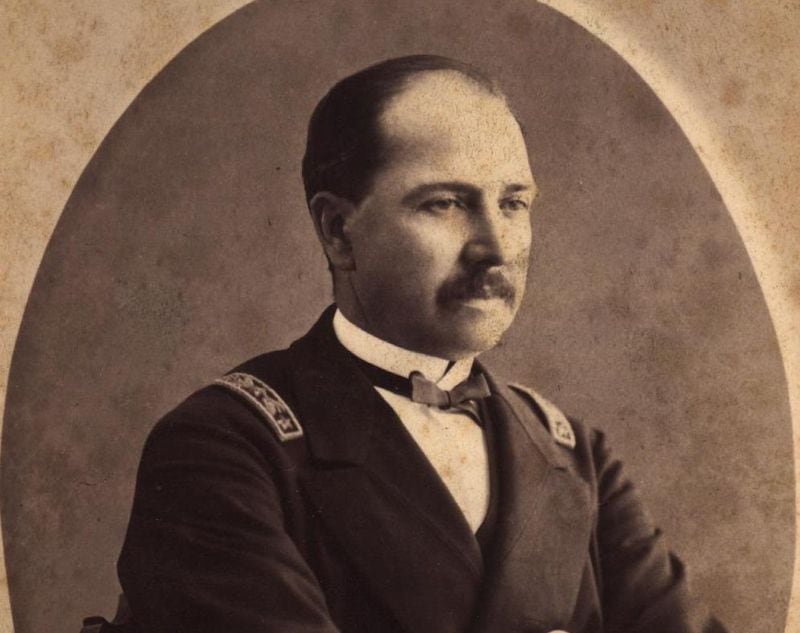

So, in charge of the ship’s captain Patrick Lynch the so-called “Lynch expedition” left Arica on September 4, 1880, on board two liners: the Copiapó, with the Buin regiment, artillery and related services; and Itata where the Talca and Colchagua battalions, as well as the cavalry, went. It carried a force of 1,900 infantry, 400 cavalry, 3 Krupp mountain guns, an engineer section and an ambulance. In total, around 2,600 soldiers.

The ships headed to the ports of Supe, Chimbote, Trujillo, Eten and Paita. At the landing, no one put up armed resistance to the landing or to the actions carried out. Strictly speaking, Meffale emphasizes, there were “only attempts to refuse to pay war contributions.” This is because the area has been virtually abandoned to its fate. Here’s how Parodi explains it: “Peru’s defeat alongside Bolivia in the Battle of Tacna destroyed the bulk of the Peruvian army, and the navy had already been defeated in the naval combat at Angamos. It was for this reason that there were virtually no fighters or military resources left and the “wandering expedition,” named after Admiral Lynch himself, encountered virtually no resistance.”

“I will have the pain of completely destroying your ingenuity”

A letter reached the hands of Arturo Darteano, the son of Dionisio, a wealthy landowner in the region. Signed by Lynch (contained in his Memories), told him without fuss: “I impose on your Palo Seco mill a war contribution of one hundred thousand pesos in money or cash equivalent to this sum. . If you do not specify this immediately, giving the corresponding orders to your employee, so that he pays the indicated contribution, I will have the trouble of completely destroying your Palo Seco mill.

Despite their status as landowners, Parodi emphasizes that the region was poor. “What Lynch found on the northern coast of Peru were landowners and ordinary citizens, already ruined by the pre-war crisis and even more so by the conflict, who were pushed into paying onerous war quotas . .

Without anyone’s help, Darteano consulted his father and they decided to pay. However, the news reached the Peruvian government, which could do little. “The government of Nicolas de Piérola found its hands tied to help the Peruvians of the northern coast of the country and His actions were almost limited to a few decrees prohibiting the payment of war quotas. which only increased the destruction,” says Parodi.

The decree provides for a sanction: “If they disobeyed them, they risked being tried for treason. In other words, the worst of all worlds. If it is not paid, destruction, if a trial for treason is paid,” says Mellafe. Faced with this, the Darteanos ultimately decided not to pay anything. This prompted Lynch to respond (recorded in his Memoirs):

“The Supreme Head of the Republic of Peru can decide what he considers appropriate in the territory subject to his sovereignty; but it cannot demand obedience in the part of the territory occupied by our arms. To assume otherwise would be to render the law of war illusory. The Supreme Leader of Peru does not save with his Decree the interests of his Lord Father, if he wanted the Supreme Leader to prevent our forces from obtaining the payment of the contributions that they have the right to demand, for his purpose, he would have It was more appropriate for him to protect with his weapons the territory threatened by our weapons.

Thus, Chilean forces dynamited the Palo Seco sugar factory and took away bags containing sugar and other goods. . The situation was repeated in the rest of northern Peru. Since very few people could pay, they suffered the consequences. Parodi emphasizes that this was transversal to Peruvian society and did not only affect the rich.

“These citizens, from all social classes, saw their farms and homes burned and destroyed, as well as robbed of their material possessions such as money, jewelry, valuables, etc. Entire ports and railways, such as the port of Chimbote and all its infrastructure, were simply razed. , also small towns that existed within the haciendas. The same thing happened, for example, in Puerto Eten.

Lynch and the Chinese

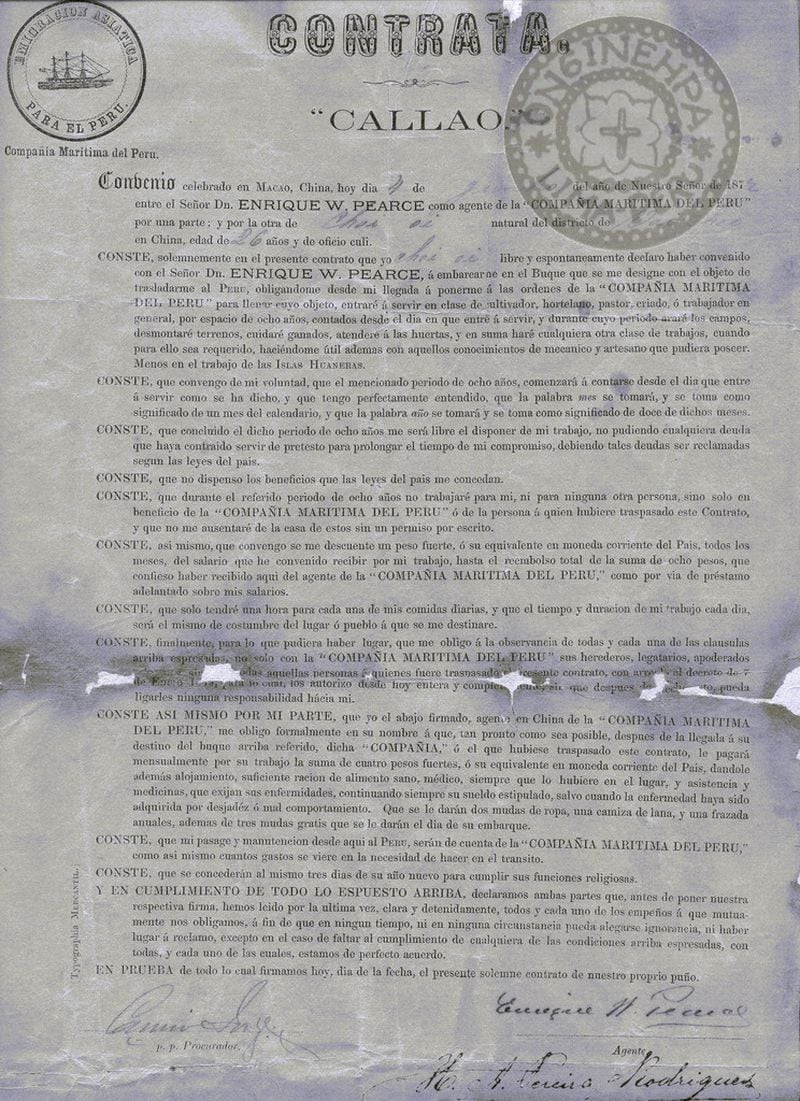

Passing through the haciendas, the Chilean troops found a surprise. Thousands of Chinese citizens worked the land in conditions of semi-slavery. “The living conditions were terrible, 200 Chinese people crammed into a warehouse that served as housing. The punishments were corporal or chained,” explains Mellafe.

Lynch decides to free them and some of them join the Chilean army. . Orientals had flocked to the region due to poor living conditions in their country. “It was a shame, and there was a mass exodus of cheap labor to California and Peru. For this, they created the “Peru Shipping Company” which hired these people in China itself and shipped them to Peru,” explains Mellafe.

As often happens, when signing a contract, a trap left the Chinese practically defenseless against those who hired them. “In the contract it says ‘that during the aforementioned eight-year period I will not work for any other person, but only for the benefit of the ‘Compagnie Maritime du Peru’,” explains Mellafe. And if you reread the two previous “Conste”, you will see that they contradict each other and that the Chinese find themselves completely powerless. »

The expedition took place between September 4 and November 1880. For Rafael Mellafe, Lynch was a success. “In my opinion, yes, the proposed task has been accomplished. Landowners in northern Peru felt like their country was at war and money and goods were brought to them. For Daniel Parodi, it is “the most controversial campaign that Chile developed during the Pacific War”.

“The devastating effects, contained in the Peruvian national memory, cannot be ignored by the liberation of the Chinese workers from the burned farms, who, in fact, lived in deplorable conditions and had replaced, a few decades ago, the slave population which worked in them. But the Lynch expedition was not, and cannot be reduced to, a liberating expedition. To claim this constitutes a serious historical falsification “.

“On other occasions, I have highlighted the difficulty of a request for forgiveness from Chile to Peru for the excesses committed during the Pacific War. -adds the Peruvian historian-. Chile is the country that achieved victory and has the right to honor its victorious heroes. However, a few gestures of empathy and solidarity in the face of these excesses, committed by governments and personalities who have no longer been with us for a long time, could pave the way for this war to finally be understood as a past event and not as a epic. … current, worthy of the nationalist historiography of the 19th century. Due to its obvious and transgressive violence, the Lynch expedition should constitute the starting point for a reconciliatory dialogue between our nations around a war that certain actors and sectors, including through social networks, seem to continue to wage in the realm of the imagination.

Continue reading in Cult

Source: Latercera

I am Robert Harris and I specialize in news media. My experience has been focused on sports journalism, particularly within the Rugby sector. I have written for various news websites in the past and currently work as an author for Athletistic, covering all things related to Rugby news.