Between April and July 1881, a Chilean expedition led by Colonel Ambrosio Letelier was sent to fight the troops and guerrillas who, after the capture of Lima, dispersed towards the sierra. But he committed outrages such as theft of money and abuses against the indigenous population, which caused him to be tried and imprisoned upon his return. As historian Gonzalo Bulnes pointed out, “it is a sad page in the Pacific War.”

Thirst increases and the hard march in the Peruvian Andes is felt by the Chilean troops, unaccustomed to the altitude and humid climate. . It was the middle of 1881, Pacific War enters a decisive phase and a group of soldiers arrives in a hamlet lost in the Andean mountains. They ask the inhabitants for food and refreshments to regain their strength before continuing on their way. A peasant woman offers them a drink. To dispel distrust of the troops, the woman takes the initiative. “He first drank the poisoned soda which he then served to a group of soldiers, who all died within minutes,” he explains. Worship the Peruvian historian Daniel Parodi.

Episodes like this detail the fierce resistance to Chilean occupation by the largely indigenous mountain dwellers. . They were simply fed up with the “quotas” or forced supplies of food and spices imposed by the troops, and worse, the looting and shooting of guerrillas – already civilians – caught in sabotage actions.

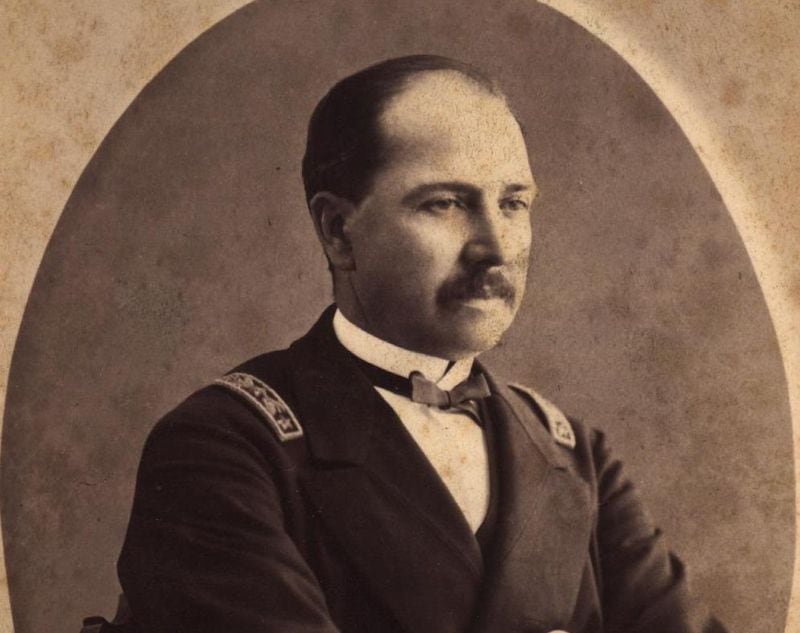

All this happened notably during the first Chilean operation in the Peruvian mountains, the Junín Expedition, between April and July 1881, but better known as the “Letelier Expedition”, named after his commander, Colonel Ambrosio Letelier . The idea was to send him to fight the troops and guerrillas who, after the capture of Lima, dispersed towards the sierra. But, in the words of historian Gonzalo Bulnes in his famous work Pacific War, “It’s a sad page in the Pacific War.”

According to Bulnes, from the beginning, the shipment had a problem. “He was neither given instructions nor assigned to any section of the police station to keep accounts, receive funds and inspect expenditures, which has no satisfactory explanation, as he was not going to carry out a search lasting a few days but to occupy a distant territory. Because of these omissions, Letelier believed himself authorized to proceed as he saw fit, using enemy territory as his own and using any means to obtain resources. “.

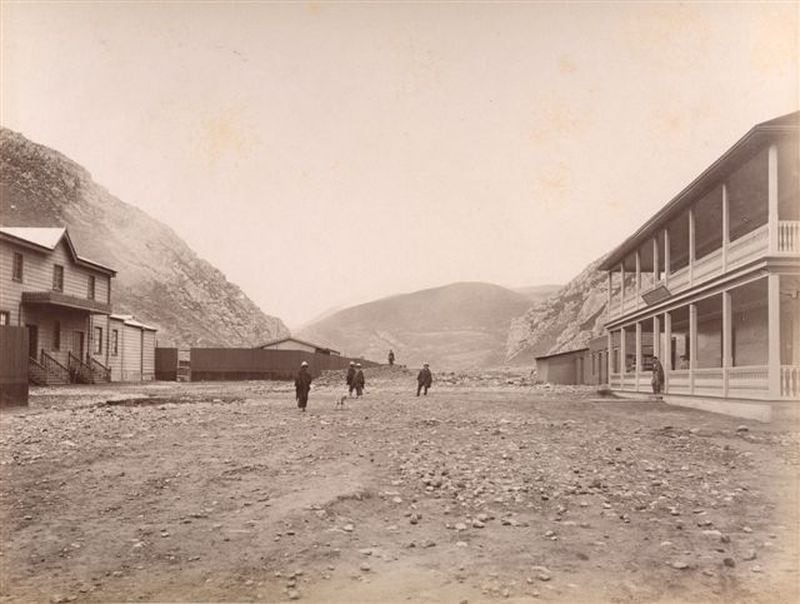

The latter is explained by the fact that, being far from Lima, the Chilean troops did not have enough clothing and food. For this reason, the Chileans had to seek supplies in the small towns located between the recesses of the Andean valleys and mountains.

“The troops sent to the mountains had to meet their needs on the ground, that is to say, their maintenance was done by imposing food quotas,” explains Rafael Mellafe. If someone didn’t deliver what was asked, it was taken away. In some cases, notably during the Ambrosio Letelier expedition, abuses were committed in this regard. . But in general, the people of the mountains had to support the Chilean forces.”

Indeed, on April 27, the expedition occupied the Cerro de Pasco and on one side, alone and Letelier declared martial law in the area. “The forces under my command will provide decisive support and protection to the people and interests of neutrals in the current war, as well as to the peaceful inhabitants of the country who have not taken up arms against the Chilean forces or aided the enemy in no other way.”

Even, as Gonzalo Bulnes recounts, Letelier even sentenced to death an Italian citizen named Emmanuelle Chiessa. , lived in Cerro de Pasco and had made Peru his adopted home, accused of having conspired. It turns out that in 1879 he had organized a military unit and donated $400 for its creation, which was considered a crime by Letelier. A military court tried him and sentenced him to death.

The gathered neighbors went to see Letelier, who they asked to commute the Italian’s sentence. The colonel agreed, but in exchange for a ransom of $50,000 in silver pesos. From theft. Chiessa had $39,000, so it was the neighbors who supplemented the amount. The problem for Letelier is that the Italian ambassador in Lima has filed a complaint with the Chilean headquarters. Letelier defended himself by saying that Chiessa “lost his neutral character because of these acts.”

Bulnes judges him harshly: “More than a military campaign, the expedition became a vast armed requisition of money, with the participation of the worst social elements. The degraded Peruvians offered to denounce their compatriots and gave information to create quota lists, denounce the hiding places of money and classify the property of those who were absent.

Resistance

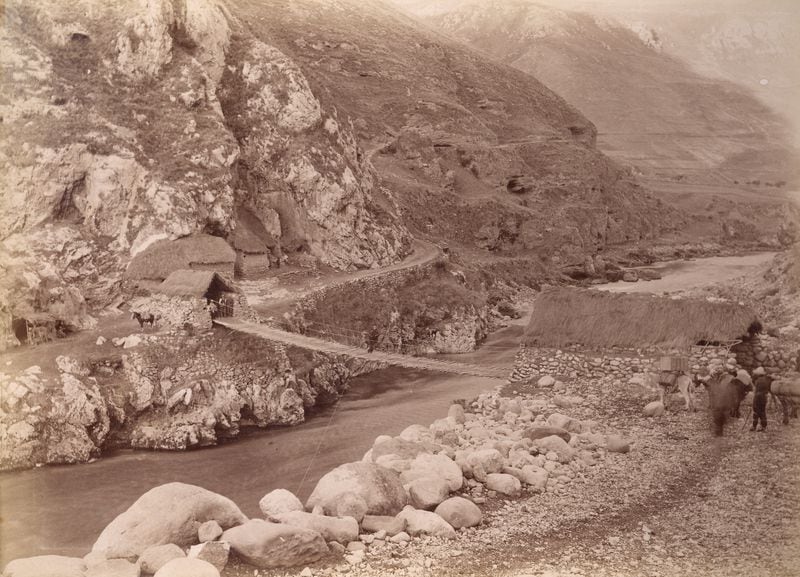

Faced with the attacks of the Letelier expedition, the peasants organized themselves into groups led by hacienda foremen, local chiefs, and even priests, to resist. . The war, which until 1882 took place in the south of the country or in Lima, had reached the heights of the Andes. “They dedicated themselves to the sabotage and constant harassment of the expeditions of Letelier and later of Del Canto -explains Daniel Parodi-. Either by the famous galgas, which were enormous stones thrown from the top of the ravines, to attack the advance guards by surprise, or to block the passage of the scattered soldiers by blowing up a bridge.

“Resistance in the Peruvian mountains has been fierce. The war knocked on the doors of the inhabitants of this region and they defended themselves as their Inca ancestors did -explains Rafael Mellafe-. This is why we see so many stories of Chilean soldiers being beheaded and their heads impaled and their bodies dismembered after battle.

The problem was that in the 19th century, war was a gentleman’s affair. . The guerrillas, not being regular troops, were not subject to international laws on belligerence. Therefore, as soon as they were captured, they were unceremoniously shot dead by the army. Then they passed through the wall, men, women and even priests, as happened in the town of Huaripampa where the local priest, Buenaventura Mendoza, organized resistance.

“Members of the Montoneras were considered stateless, that is, they did not fight under a flag but rather for themselves or to follow a leader, so the laws of war of the time did not punish not shooting them,” says Mellafe. . However, this practice was not common, it was only used in certain cases during the Del Canto expedition in the mountains, but it was massive after the Battle of Huamachuco (July 10, 1883) where the order given by Lynch to Gorostiaga was to “take no prisoners.”

The burning atmosphere of the mountains was taken advantage of by General Andrés Avelino Cáceres . Hidden in the mountains, he organized an army with the remnants of the troops who had defended Lima and the recruits who quickly swelled their ranks, especially after suffering abuse from Chilean soldiers. Its appearance will therefore be frequent until the end of the war.

Due to her control of the territory and the surprise of the Montoneras attacks, the Chilean troops nicknamed her in a particular way: the “witch of the Andes”.

The end

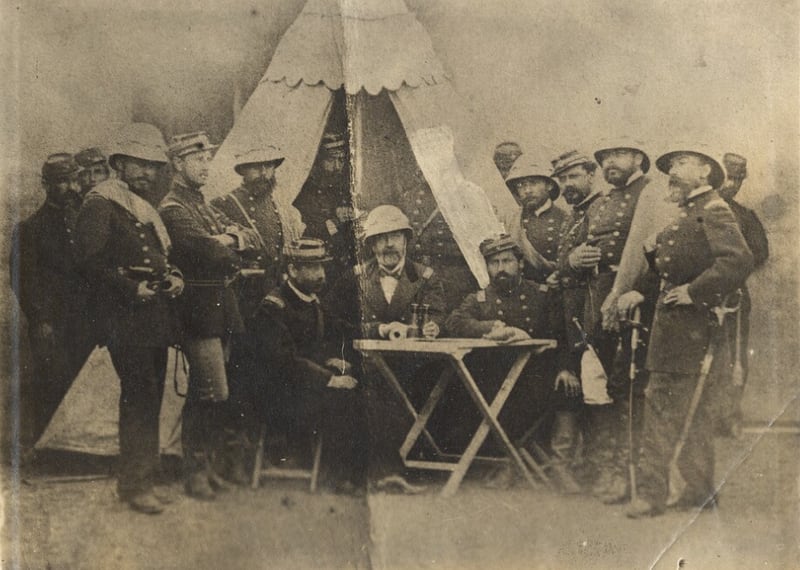

In May 1881, and the captain of the ship, Patrick Lynch , takes command of the occupying army in Lima. “One of his first measures was to ask Santiago for permission to bring Letelier back to Lima as quickly as possible and to avoid the demands with which the foreigners were besieging him,” Bulnes explains. He did so on May 22, and with the only response that “they had sent the order” to Letelier, he reiterated the instruction a week later. He received no response.

Due to slow communications or otherwise, Letelier said the first order did not arrive until June 7 and the second on June 9. . This caused the surprise of Lynch “who could not explain how one of his orders… took fifteen days to reach Cerro de Pasco”. Then Lynch began to hesitate. “Doubt arose that this was a pretext for not withdrawing from the places he occupied,” and these suspicions were confirmed when Letelier asked him to further extend the expedition. Lynch told him there was nothing he could do and to come back immediately.

A month after the first order, Letelier still had not left the premises . Lynch wired to inform Santiago. This was open insubordination. His excuse was that there were issues holding him back. He even sent reports that 80 Chileans had fought against 5,000 natives, whom he had defeated with only 2 of his own dead and 1,500 Peruvian casualties. Lynch, of course, did not believe any of Letelier’s exaggerated news and ordered him to return.

Finally, Letelier returned to Lima on July 4, 1881, almost two months after the first order he received. , and Lynch reprimanded him severely. “He reproached him for his behavior towards the populations and was determined to take all measures to restore discipline and morale.” And he did it. Letelier prosecuted for embezzlement, imprisoned and sent to Santiago , where he appealed the conviction to the Supreme Court. This ultimately overturned the prison sentences handed down by the Lima military court.

Then, a second expedition was sent to the Sierra, under the command of General Estanislao Del Canto , between February and July 1882. It was as part of this adventure that 77 soldiers who remained in the town of Concepción, waiting to be picked up by the main body of troops, were massacred with rage in memory fight of La Concepción , July 9 and 10, 1882. The anger of the victors, in particular of the suffering natives, was expressed with ferocity by the mutilation of the bodies. In a way, they took revenge for the abuse they had suffered. But this is another story.

Continue reading in Cult

Source: Latercera

I am Robert Harris and I specialize in news media. My experience has been focused on sports journalism, particularly within the Rugby sector. I have written for various news websites in the past and currently work as an author for Athletistic, covering all things related to Rugby news.