The autobiography of Rush’s bassist and singer reveals surprising episodes in the Canadian trio’s career, supposedly far from the traditional excesses of rock. There is also a mention of Chile.

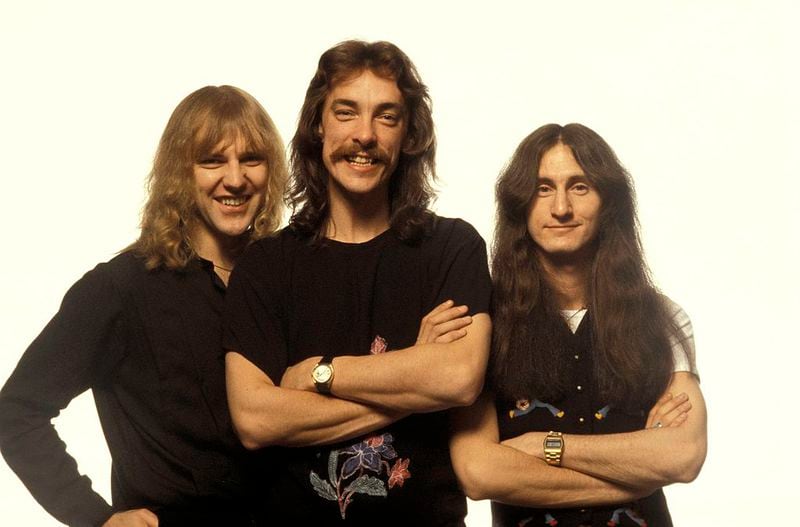

For decades, Rushing was vilified with particular glee by the specialist press, as an example of the worst that rock could offer in an unbearable cross between metal and progressive, genres perpetually rejected by critics – owner of a caviar palace, suppose – we say – as a representation of the uncool. . The virtuosities, science fiction, mythology, literary references and philosophical alliances, all crowned by the sharp voice of Geddy Lee, made the trio an ideal target despite millionaire sales, the avowed admiration of various artists such as Metallica and Jeff Buckley, and a legion of devotees.

“The twilight of the geek gods”, headlined Rolling Stone magazine in June 2015, on the only cover given to Canadians, ignoring the sustained success in the United States for many years between the 70s and the final tour in 2015, without having of singles adapted to the public. radio and the favor of journalism. The title reiterated the music columnist’s usual, looking-over-his-shoulder judgment: Rush as the cheesy, quintessentially boring incarnation.

Geddy Lee’s recent autobiography My effin’ life This won’t convince the detractors, but it reveals habits and events typical of the vast majority of rock artists from the genre’s golden age. There probably wasn’t much sex on Rush’s many tours, but when it came to drug and alcohol use and settling scores with rivals, the Canadians were like any band .

nosebleed

The fans know it A visit to Bangkok from the album 2112 (1976), tells a fictional journey through some of the most recognized cannabis destinations on the planet. What we didn’t know is that psychotropic substances and chemicals were part of the early recipe book of the group founded in 1968. Lee reveals that since adolescence, the different line-ups of Rush, before the definitive line-up with Alex Lifeson on guitar and Neil Peart on drums, were prone to the habitual consumption of LSD, STP (dimethoxyamphetamine) and hallucinogenic mushrooms.

With nuances, tobacco has accompanied practically the entire career of the group. While Lee smoked a pack a day – he quit in 1983 – Peart lit up cigarettes for the rest of his life.

Alcohol was also common in Rush’s existence with periods where its consumption made the tour staff unruly with some problematic instances and memorable drunkenness of the band members, including an episode of destruction and attack on the security staff at a Manchester hotel. , after drinking a dozen shorts of cognac.

The bassist especially remembers the alcoholic reels with groups like Thin Lizzy – whose leader Phil Lynott died of alcohol in 1986 – and UFO. Pete Way, the latter’s bassist (an influence on the look of Iron Maiden’s Steve Harris), became friends with Lee. In addition to advising him not to listen to progressive rock, Way mocked Rush’s convoluted compositions as Xanadu . At one show, Lee discovered that Pete had nailed slippers to the side of his Moog pedal board to go with his circa 1977 outfit, a satin dress. In turn, Lee burst out laughing every time he heard UFO’s bass stop playing, a clear sign that Pete was drunk.

As Lee reveals, the darkness Steel caress (1975) was composed under the influence of hashish. “It had a lot less echo than we thought (…) it sounded more reverberant than it actually was.”

Beginning in 1977, when Rush began to lead tours with an annual schedule of two concerts every three days, the crew took a deep dive into cocaine. “We were so numb from the endless car trips and almost nightly concerts,” says the musician, “that a quick energy boost seemed practical.”

So from 1977 until the early 1980s, Geddy Lee was hooked. Although he gave up using marijuana “because it made me paranoid” and considered himself “more conservative than my peers when it came to recreational drugs”, Lifeson flirted with ecstasy in the 1990s, while Peart stocked tobacco, weed and whiskey during his tours. – Geddy Lee even wore a chain around his neck with a musical note pendant, necessary to apply the doses.

“I wasn’t prepared,” he admits, “to know how addicted cocaine was going to make me. »

Lee takes advantage of the drum solos or the break before the encore to breathe a few lines. Believing that at home he would get rid of drugs, he realized that his wife and his friends linked to the world of fashion and design were in the same orbit.

This habit began to affect his voice. “The more coke I consumed, the more cigarettes I smoked, which gave me a very bad cough and also problems sleeping.”

Rush’s road crew was used to it, too. A driver began drawing stripes on the equipment, while roadies and musicians waited their turn. “I knew I was hurting myself…my nose was bleeding and scabs were coming out, but despite my instincts I continued to do it.”

The atmosphere of the tours was starting to become rarer with questionable characters behind the scenes. After a show in the Midwest, Lee boarded his bus to find a drug dealer set up with a briefcase, a weight and a satellite phone. They soon learned that the FBI was following the dealer’s trail.

Health issues, scattered events where the only thing that mattered was traffic jams, and an episode in Texas where Lee and a friend met a girl carrying coke, took her to the tour bus, snorted the drug and threw her out, were the definitive alarms to gradually abandon the white goddess.

Fuck you Bill

Geddy Lee says that although he was taught never to speak ill of the dead, he says “fuck you” when he mentions the legendary promoter Bill Graham, who died in 1991, one of the most recognized in the American scene; master and lord in San Francisco, responsible for transforming venues like the Fillmore and Winterland ballrooms into rock sanctuaries.

They had several meetings. The first in 1975, when Rush opened for Kiss. The special guests were the Tubes, Graham’s favorites, so much so that he gave them absolute preference in treatment, at the expense of the others. A promoter’s roadie negligently damaged an Alex Lifeson amplifier. The guitarist furiously pursued Graham, demanding – in vain – that he take charge.

“What would have cost him a hundred dollars that day,” Lee reflects, “set the tone of our relationship forever.”

In 1976, on a shared date with Ted Nugent and the English group Be-Bop Deluxe, Bill Graham’s team stopped the signature music that introduced the trio to introduce them as Mahogany Rush, the group of Canadian guitarist Frank Marino.

The next meeting was at Winterland in 1977, with the trio headlining a shared date with UFO and Max Webster. “We found out he had unearthed a local band called, I’m not kidding, Hush,” the bassist says.

Determined to get revenge, Rush began planning his West Coast tours, avoiding Bill Graham’s estate. When the trio became famous in the United States with Moving images (1981) – third place on the Billboard 200 – a few sold out shows at the Cow Palace, Bill Graham showed up with a batch of Napa Valley wines with a label reading “30,000 Bay Area fans can’t be wrong . » The members of Rush greeted him with fake smiles.

In 2013, it was time to settle scores with Jann Wenner, the creator of Rolling Stone magazine, when Rush was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The journalist and businessman boasted of excluding Canadians from the entity he led for decades, despite the fact that the group could be among the nominees since 1998, and the declared influence exerted on the elite rock from the 90s, with explicit recognition of the artists. like Nine Inch Nails, Tool, The Smashing Pumpkins, Primus, Pantera and Rage Against the machine, among others.

Wenner barely said “from Toronto” during the ceremony , the site collapsed amid cheers and applause. The vast majority of those in attendance were there for Rush and, in doing so, to rub Wenner in the face for his stubbornness. The now disgraced leader approached the trio’s table.

“Amazing,” he whispered to Lee.

“The man (…) who boasted of having single-handedly kept us away from this sacred room (and of having practically ignored us in his magazine) – writes the bassist – was visibly shaken (… ) I admit that it was also a very sweet moment.

The bitter farewell

Although Geddy Lee admits that meetings with Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart can be counted on the fingers of one hand in more than 40 years – they decided early on to share their rights equally – the R40 tour had a prologue and a bitter epilogue for the singer. , bassist and keyboardist.

Peart, convinced that the group had reached a creative peak impossible to surpass with the last album Mechanical angels (2012), and that his endurance would soon not allow him to organize marathon concerts, he expressed in 2014 to the group and manager Ray Daniels the desire not to go on tour the following year. At the same time, he dropped plans to retire. Lifeson said that due to his health problems, including arthritis, he was seriously considering stopping performing live. For this reason, I preferred to organize a visit as soon as possible. Neil Peart barely hid his anger and Geddy Lee was stunned. His lifelong band had an expiration date around the corner.

The musician’s sadness increased when he learned that there would only be 35 dates in just over three months, the most the manager managed to negotiate with Peart. His desires to visit Europe and South America were buried. It must be said that in the book, Lee describes the Chilean public as “absolutely incredible” because of the show offered at the National Stadium in October 2010.

As the tour progressed, the atmosphere became more and more somber. The only one who really seemed happy was the revered drummer. Even Lifeson, recovered from his ailments, was disappointed not to extend the tour. “He was the only person in the entire organization who felt happier with each step toward the end,” Lee writes.

When the final date arrived on August 1, 2015 at the Los Angeles Forum, Peart virtually ignored his teammates by handing over his locker room to family and friends. After the show ended, he did not attend the team party and, in fact, did not see Lee and Lifeson again until a year later, after revealing the brain cancer he suffered from.

Shortly before his death on January 7, 2020, Neil Peart reviewed Rush’s discography. Every day he went to his office to listen to each album. In the twilight of his life, he let his comrades and friends know how proud he was of all of his work.

More than revenge, the nerds had triumphed by turning everything upside down.

Continue reading in worship:

Source: Latercera

I am Robert Harris and I specialize in news media. My experience has been focused on sports journalism, particularly within the Rugby sector. I have written for various news websites in the past and currently work as an author for Athletistic, covering all things related to Rugby news.