In July 1931, after learning of the catastrophic situation of the country’s finances, the government of Carlos Ibáñez del Campo began to waver. Chile, hard hit by the consequences of the Great Depression, is in crisis. The iron authoritarianism of the “horse” only inflamed tempers and protests arose. People had to climb trees to avoid police charges and deaths were attributed to police officers. Eventually Ibáñez had to leave the country and people took to the streets to celebrate.

In her own handwriting, the writer María Luisa Fernández detailed the events of the deep social and economic crisis that Chile went through in a letter dated August 7, 1931, addressed to her son, the poet Vicente Huidobro, then already a household name. in the artistic avant-gardes. The writing was compressed and seemed to overflow every space of the paper, as if Fernández did not want to lose the opportunity to refer to a detail. Especially when we talk about the fate of President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo. “The unfortunate dictator is gone -he noted in the letter available in the writer’s file. He left between the roosters and midnight fleeing after leaving the people dripping with blood.

Ibáñez, nicknamed the “horse” for his skill as a rider (and his stubborn character), had taken the train to Argentina . He resigned from the presidency after days of massive protests in the streets, in which professional associations, universities and ordinary citizens united to express their discontent. At that time, the country was hit by the ravages of the Great Depression, the economic crisis that was raging in the world economies and which would have a strong impact on the country.

The milestone was the one that marked the start of the satirical magazine Topaze, the so-called “barometer of Chilean politics”. The first issue hit the streets on August 12 of the same year, with resounding commercial success. a caricature of Ibáñez alongside Argentinian President José Félix Uriburu, who headed a de facto government.

It happened that from one moment to another, the economy of the country collapsed. An unexpected scenario just a few months away, when Ibáñez himself expressed confidence that the Great Depression had been contained. “It is very flattering to me that the occasional circumstances, which the whole world is going through, have been alleviated in Chile thanks to a tough economic policy” he declared in his New Year’s message of 1931. While in New York, the unemployed lined up and the factories closed their heavy doors, following the stock market crash of October 1929. The crisis was the problem from someone else.

But this optimism was fleeting. In the north, nitrate mines were already feeling the impact on demand for raw materials, the main export of countries like Chile. According to Collier and Sater in their good book Chilean History 1808-1994 If in 1925, the exploitation of saltpetre employed 60,000 people, in 1932, it only fed 8,000 workers.

Due to the crisis, nations stopped buying. Commodity prices on the world market have fallen; as Cariola and Sunkel detail in their book A century of economic history in Chile, if in 1917 US$110 per ton of nitrate were paid, then in 1930 the market value was only US$53. This dealt a final blow to declining nitrate production.

The widely cited study by the League of Nations (the predecessor of the current UN), called the World Economic Survey 1923-1933, pointed out that Chile was the country hardest hit in the world by the recession. The “strict economic policy” was not enough. The crisis appeared, fast, violent and implacable on the population.

Ibáñez’s ambitious public works program, and the Treasury in general, was based on export taxes and credits claimed abroad those that could not be renewed. “There was a triple economic and social disaster . Tax deficit, unemployment and lack of foreign currency”, explains Augusto Millán in his History of gold mining in Chile. The government had to suspend payment of the foreign debt which, due to international fluctuations, had skyrocketed and was now unpayable. In short, Chile had no peso.

That’s when we had recourse to “economic policy”. “Ibáñez and his advisers tried first with the traditional panaceas: reduction of expenses with an increase in taxes on exports – retail Collier and Sater -. However, no matter how quickly and drastically he cut spending, Ibáñez was unable to cover the deficit.

Meanwhile, the “horse” has not given up on maintaining press censorship and the persecution of opponents and political parties (like the CP) to silence the home front. Moreover, taking advantage of a legal vacuum, he had all the members of the National Congress appointed himself, to the “Thermal Congress” in question.

Towards the middle of 1931 the situation justly became critical. . Ibáñez decided to change cabinet, summoning the radical Juan Esteban Montero (from the moderate wing of radicalism) for the Interior and Pedro Blanquier for the Ministry of Finance. Montero, a lawyer and academic with a spirit of dialogue, decided to lift some restrictions on the press in order to report what was happening. It was obvious anyway; the country was in crisis.

protests break out

just the minister Blanquier admitted to the press the huge budget deficit that the country had accumulated, public opinion began to react . The first demonstrations then registered; university students mobilized and there were clashes in the streets with members of the Carabinieri (an institution founded by Ibáñez himself in 1927). Out of solidarity, some professional associations have joined.

“Students from the University of Chile and the Catholic University went on strike -Point Collar & Sater-. Professional associations, starting with doctors and lawyers, declared their solidarity. The inevitable riots were tightly controlled by the police; about ten people were killed. The movement spiraled out of control and the regime was forced to surrender in the face of civil protests.

The protests were harshly repressed by the government. So much so that people had to climb trees to avoid being hit by a police projectile. And it ended up happening. July 24, medical student Jaime Pinto Riesco he fell dead, according to the magazine Zig Zag n° 1380, under the bullets of the police. This further angered tempers and the Medical College went on strike. In her letter, María Luisa Fernández says that Pinto “He was distributing proclamations at the door of the San Vicente Hospital (Editor’s note: today the School of Medicine of the University of Chile) when a policeman shot him in the back.”

The following day, his funeral at the General Cemetery was massive and turned into another day of protests against Ibáñez. The police arrived and in the middle of the fight another was killed, the professor of the Liceo de Aplicación Alberto Zañartu. Now the teachers’ union has joined the strike.

The situation, between protests, marches and repression, could not believe it. The entire ministerial cabinet resigned. Ibáñez realized that he had been left alone and had lost control of events, so on July 26, 1931, he handed over power to Senate President Pedro Opaso Letelier, asked Congress for permission to leave the country for a year and the next day he boarded the railroad bound for exile in Argentina. However, the legislature did not give him permission and expelled him for leaving Chile without his permission.

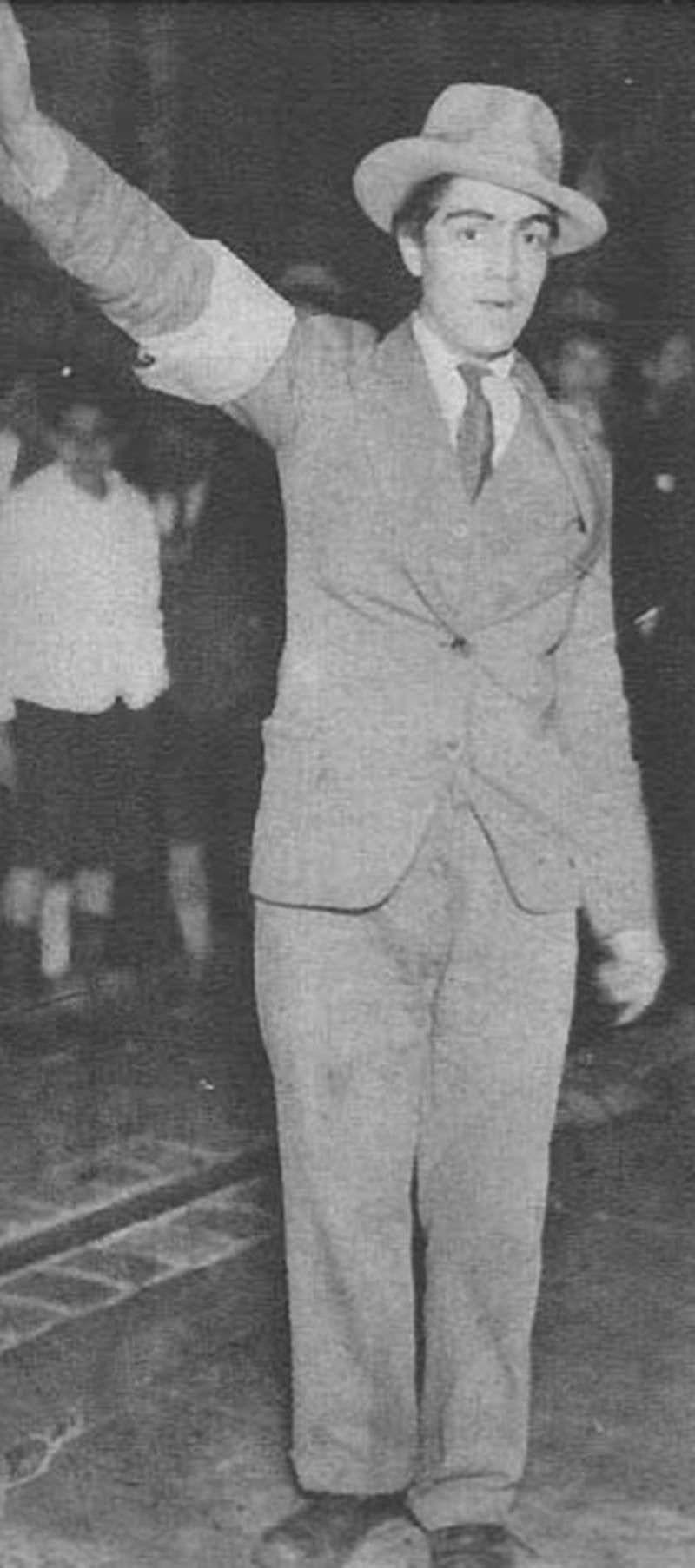

In his Memoirs, former President Eduardo Frei Montalva , then leader of the students of the PUC -with Bernardo Leighton-, tells how this day was lived in the capital. “On July 26, the day of his departure, the enthusiasm exploded out of control. People hug in the streets, columns of demonstrators converge on the center, chanting and shouting…no member of the armed forces took to the streets, which were left in the hands of the crowd. However, there were no attacks or violence. College students, wearing white armbands, directed traffic. there was nothing to regret ”.

What Frei says is true. At that time, spontaneous citizen guards were formed of men and women (even without political rights, let us remember) who supported the direction of traffic, in the face of the discredit of uniformed police officers who remained confined to their police stations. “Order has been restored, young people and children have taken over the duties of the police. guarding the city and directing traffic like the most expert,” noted María Luisa Fernández in her letter.

The departure of Ibáñez decompressed the situation . An audiovisual recording by an unknown author, titled The fall of a regime , documented the hubbub and massive protests to celebrate Ibáñez’s resignation. Little did they know it then, but the country would have a turbulent year before it regained stability; a period of riots, attempts to establish a socialist republic, resignations and tensions between various groups who disputed the leadership of the deep crisis from which he emerged only after several years and modified the social pact for the decades to come. But this is another story.

Continue reading in Worship

Source: Latercera

I’m Rose Brown , a journalist and writer with over 10 years of experience in the news industry. I specialize in covering tennis-related news for Athletistic, a leading sports media website. My writing is highly regarded for its quick turnaround and accuracy, as well as my ability to tell compelling stories about the sport.