Little by little, it became common for coffee to indicate the place in the world it comes from. Is a cereal from Colombia very different from one from Ethiopia? Although it is not the only factor, here we explain how it determines its character and flavor.

Drinking coffee is becoming an increasingly complex pleasure. Perhaps this has always been the case, but it is only now, seven hundred years after the practice became popular in Arabia, that we realize that what we called for decades “coffee drinking” – pouring hot water over a few teaspoons of instant powder – was just a sad simulation. . Drinking coffee, in reality, is much more than drinking it: it is knowing how to extract or filter it using different methods; It is knowing how to grind the grain of the appropriate particle size according to the chosen method; and it is knowing how to differentiate from which country this grain comes to see what flavors and sensations we will obtain from this black drink.

The latter, which may seem the most snobbish of concerns, is not intended for those immersed in the incessant and addictive search for the perfect homemade coffee. A path that begins but never ends, since another variable always appears that can change the character, sweetness and profile of what you drink.

Just as wine lovers choose their bottles based on the grape variety and the valley where the grapes grow, coffee lovers increasingly care about the origin of the beans, where they were grown and therefore of your climate, your land and your altitude. will affect the experience.

So says Gabriela Sanhueza, barista and store manager at Coffee Workshop in Valparaíso, we talk about “traceability”. It’s about managing the greater amount of information about the coffee you buy and drink: not only the country and region it comes from, but also the fermentation process it receives – washed or natural – , down to the name of the farm and producer. same coffee producer. “I even hope I have the producer’s zodiac sign,” Sanhueza says, half joking and half seriously.

The more complete this presentation of information, the more possibilities there are to guarantee both the quality of the coffee and its characteristics and how to take advantage of them. Especially for roasters who, with all these cards on the table, can do a better job and get the most out of the bean.

“The real magic happens in the roasting,” says Juan Pablo Cañas, brand manager from Nescafé, a brand that has just launched its range of ground coffee for extraction in Chile, which does not mean that the origin of the bean does not matter to the consumer.

Arabica vs. Robusta

Before knowing where it comes from, it is necessary to distinguish the two main species of coffee grown in the world. The queen is Arabica – it represents more than 60% of global production – which has a more elongated bean and generally produces a much more delicate drink, with fruity and sweet flavors. It is more valued because its cultivation is more complex and less productive; it generally requires altitude – we can hope for more than 1,000 meters above sea level – and a rainy, not very hot climate.

Robusta, on the other hand, delivers a round bean and a more bitter and caffeinated coffee. Its flavor is less acidic and fruity than that of Arabica, and more marked by wood and nuts. As its production is simpler – the trees are more resistant to diseases and different climates – it has less value on the market, being used more for the production of instant coffee or to fill cheaper blends, although good beans of Robusta are also intended for Italy. loaded, bitter and caffeinated espressos.

Each species, of course, has its own varieties – such as FL34, caturra or geisha, Arabica; the conilón or niaouli, from Robusta—, which present different profiles, perceptible for those who already have a more developed palate.

The belt

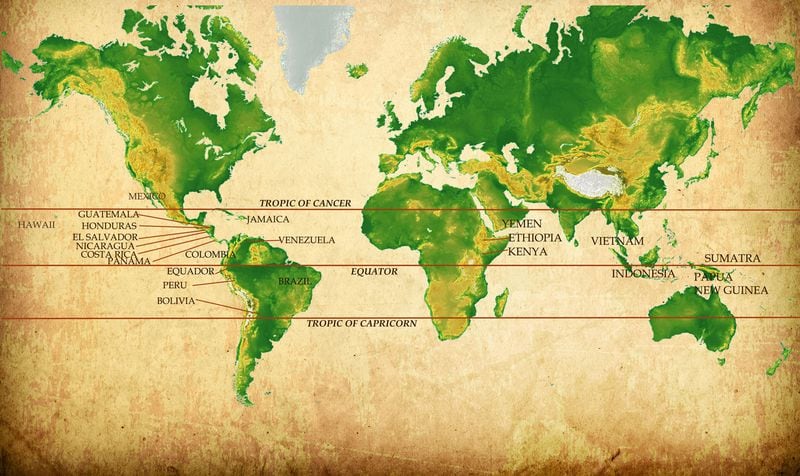

Why does good coffee always seem to come from the same countries? Destinations are repeated because coffee doesn’t grow anywhere: it needs specific climatic conditions that only exist in the so-called “coffee belt”, the tropical zone “which covers the entire line of the equator, between parallels 24º north and 24º south. Cañas explains.

In this band – which in America extends from the south of Mexico to the south of Brazil – and depending on the geographical and climatic conditions – in the deserts and savannahs of Africa for example, cereals do not grow very well – it is where all the coffee in the world is produced. Brazil and Vietnam are the main world producers in volume, dedicated in particular to Robusta, while in Arabica countries like Colombia, Ethiopia, Honduras and Peru .

“Arabicas have different profiles depending on the country,” explains Cañas. “Colombian Arabica tends to be fruitier and has a distinctive acidity. That of Africa, on the other hand, from Kenya or Burundi for example, tends to be more lemony and less full-bodied and intense.

These distinctive characteristics, according to Sanhueza, are no longer as predominant. “Before we used to say ‘Africans: acidic, lemony, they break your teeth;’ or the Colombians: very fruity and juicy,” but now that doesn’t always happen,” he explains. This has changed with the ultra-specification that exists in almost all producing countries, where each farm has its own styles, in addition to implementing different processing methods.

“What is most important to know today, more than the origin or the variety, is the process,” explains the Taller Café specialist. The most common processes are two: natural and washed.

The first is so called because the cherry (or cherry) grains once harvested, which are left to dry in the sun for several weeks, with virtually no intervention from machinery or technology. This process is used more in Robusta grains and in less rainy areas, such as certain regions of Brazil or Africa.

“Coffees from a natural process have more body, they are more intense,” explains Sanhueza. “In Brazil, because of water resources, their coffees are usually natural, and that’s why they have more chocolatey and sweeter notes.”

In the washing process, however, the cherry is separated from the grain and then allowed to ferment in water to release the mucilage, a layer that covers the grain. “When washing, the acidity of the coffee increases and the bitterness decreases,” explains Sanhueza, which allows more complex flavor profiles to be distinguished, which must be used by the roaster.

Don’t generalize

Defining all Colombian or Kenyan coffee in a few adjectives would be like trying to classify all Chilean wine in a few adjectives: an impossible, even ridiculous, task. But if we generalize, some commonalities can be established, or at least some characteristics that we can expect to find in the beans of each country or zone.

In Central America, for example, the higher the coffee is grown, the more aroma one can expect. Like the so-called Strictly cultivated (SHG, or “strictly raised”) from the Montecillos region of Honduras, grown at over 1,400 meters above sea level, and have a velvety body and lively acidity, with sweeter notes that include apricot, citrus, peach and caramel.

“Central American coffee is of very good quality and therefore very selected,” explains Cañas. “These are smaller roasters and specialty coffee shops.”

That of Colombia, as we said, cannot be classified due to its very great variety, but Sanhueza makes the effort: “they tend to be washed, with a lively acidity, more pleasant, juicy and clean in mouth. Cleaner and also with more exotic flavors.

Peruvian coffees have a similar range and not so much Brazilian coffees, which as they do not grow at such high altitudes and dry naturally, we instead find “more chocolatey and sweeter” coffees, less acidic and fruity.

Source: Latercera

I’m Rose Brown , a journalist and writer with over 10 years of experience in the news industry. I specialize in covering tennis-related news for Athletistic, a leading sports media website. My writing is highly regarded for its quick turnaround and accuracy, as well as my ability to tell compelling stories about the sport.