The celebration of Christmas has undergone several changes from the colonial period to the present day. From a popular festival, with disturbances in the streets, animals in churches and gifts of flowers and fruit, it evolved towards the end of the 19th century to become an intimate and pious celebration including toys and pine trees, d European inspiration. It was then that gifts became the center of the celebration.

At other times, the Christmas was confused with the National holidays . As was the case in September, the Alameda was filled with street stands and small ramadas, where diners enjoyed seasonal fruits, fritangas and the inevitable “spiritual drinks,” as the alcohol was called at the time. era. The founding event of Christianity was celebrated as a great popular festival.

In this Chile, that of the mid-19th century, the construction of Christmas as a religious festival during the colonial era still resonated. That is to say that it had a carnival content, in accordance with the popular festivals of the time with brotherhoods, corporals and nocturnal processions. This is why it retained this character even in the first years of the Republic. Moreover, with the coincidence with the summer season.

” Christmas party, It was a time of popular celebration where the celebration of the birth of Christ mixed with popular debauchery. and its manifestations in public spaces, whether in the Restoration Square, on the Alameda de Santiago or in the main streets of provincial towns,” explains historian Milton Godoy.

At that time, there was already a custom of giving gifts That is, he was not always associated with the figure of the Old Easter Man and his subsequent image formed in the advertising language of the 20th century. But if today gifts range from bicycles to game consoles, back then nature was the main source of offerings.

“Flowers and fruits constitute the offerings to the child Jesus in the lanterns and mangers.” , and they were also the favorite gift of those who love each other. Men gave basil to little girls and the virgin’s peaches and seasonal figs were given to adults and children,” explains academic and historian Olaya Sanfuentes in her article. Christmas tensions: Changes and permanences in the celebration of Christmas in Santiago in the 19th century.

But Chileans of the time took seriously the fact that it was Christmas Eve. Far from religious solemnity, the nativity was the occasion for a long night of rejoicing in the chinganas and inns built in the center of the capital, near the area of residence of the ruling elite. “In the popular world, Christmas was another festive period in which people drank and attended the multiplicity of chinganas, bodegones and cuisines to celebrate like any other national holiday of the time,” adds Milton Godoy.

“Custom established that Christmas Eve was not a night of sleep.” – explains the historian Elisa Silva Guzmán in her article on Christmas Eve at the Alameda-. The spirits prepared for a sleepless night, walking, eating, dancing, largely around consumption. For this, the crowds went to the Square of Abastos, to carry out their “practices contracted by an immemorial habit”, ready to spend without limits what they did not need. »

For his part, Godoy has just published an interesting study on popular festivities in the northern region of Chico, entitled Mining and festive world in the north of the country. In this context, the historian specifies that in the region, Christmas coincided with one of the main local festivals, which gave it another character.

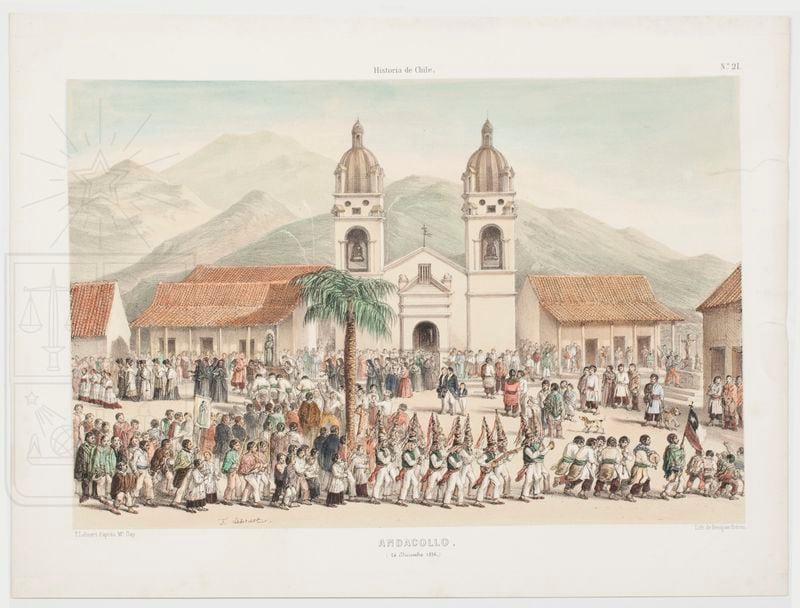

“In Norte Chico and more particularly in Andacollo, the popular festive expressions of Christmas overlapped with the local celebration since, between December 23 and 27, “The feast of Our Lady of the Rosary of Andacollo was celebrated, par excellence the greatest feast of the region.” , Explain. “A large floating population settled in the city; in 1862 it numbered around 20,000, with devotees and non-devotees of the Virgin meeting there to satisfy ‘their worldly pleasures’.”

The historian also quotes a columnist from a local newspaper, who describes what the celebration of Christmas was like in 1870, in La Serena. There the differences between the social groups of the time are realized. “Two types of fashion stood out: in the theater aristocratic fashion with gloves, Japanese bows, dresses full of fantastic decorations. ; On the sides of the Alameda there are ponchos and brightly colored costumes with seal flowers in their hair. Zamacuecas, songs and also a Turkish collection [borracheras]» .

It was not just drunkards, fruits and chinganas that were part of the celebration. IAccounts from the time describe people being in temples with animals, such as pigs and chickens. , who were forced to shout to represent the Christmas nativity scene. They were part of agrarian and rural Chile, still very present in the middle of the century.

Others were simply dedicated to shouting, imitating animal sounds, and the most excited ones played whistles and other instruments. “It was a thunderous noise composed of imitations of various animals, accompanied by whistles, whistles, piccolos . It was to recall the stable in which the baby Jesus was born,” explains Sanfuentes.

From the crib to the pines

But the chinganas, the animal noise of masses and the drunks in the streets ended up making the elites uncomfortable. Towards the end of the 19th century, in the midst of the expansion of the saltpeter cycle, efforts began to regulate and control Christmas festivities to make them less strident and intimate. “The tensions raised between the popular sectors and the elites are part of the context of an ordering conception of public space and cultural discipline. which they attempted to apply to transform popular festive practices,” explains Milton Godoy.

“These questions and directives of control emanated both from the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, which explained popular expressions as pagan acts, and from the political sectors of the elite, which understood the public and popular celebration of Christmas as another expression of necessary customs. “transform for the good of civilization,” he adds.

That is to say, it was a questioning of the way in which people separated during civic festivals. “The central point of the criticism of popular festivals formulated by the authorities in the second half of the 19th century was with the same tenor which questioned ‘excesses’, drunkenness occupation of public space and disorders of other festivities, such as carnival or the 18th, festivities in which clashes and attacks against public authority were not rare, and it was not strange either that in moments of political and social rupture festivities “Christmas lent itself to unrest and worker uprisings, as happened in Copiapó in the middle of Christmas 1851,” explains the historian.

The tension between elites and popular subjects was part of a deeper process. According to Godoy “Christmas is part of a great process of transformation of the festive world that has occurred in Chile since 1840 and deepened in the second half of the 19th century.” And there are customs, such as the installation of crèches, which bear witness to part of this transformation. Nothing strange in a society which, at that time, was evolving from tradition – rooted in the peasant and rural world – towards a modernization guided by the secular religion of the liberal elite, progress.

“The crèche has deep popular and public roots. part of colonial and baroque Catholicism, where the birth of Jesus was offered and celebrated, part of popular celebrations in open spaces and churches that featured their own richly made and decorated nativity scenes,” explains Godoy.

However, as the historian details in his new study, Little by little, this tradition began to change, as did society. The modernization and capitalist expansion of the country took place with a European accent, due to the influence of immigration and prominent models; France in culture and political model, United Kingdom in commerce and navy. In this way, Christmas began to have a public and private language closer to what we know today, with manicured Christmas trees and celebrations at home.

“As part of the process of transformation and modernization promoted by the 19th century elite The celebration has become a private and family moment around the nativity scene or the representation of the birth of Jesus. , contrasted with the public celebration which persisted, but tended to separate these two realities – details Milton Godoy -. In this way, the privatization of the Christmas celebration is part of the vast process of transformation of society driven by the elites who, in “their ardent objective of Europeanization of Chilean society, have sought to totally assimilate its modus vivendi”.

In this way, towards the end of the 19th century, the tradition (and importance) of gift-giving also transformed. “At that time, Easter and New Year gifts were mainly Parisian treats. During the last decade of the century, the practice of giving these imported objects moved from a reality between adults that occurred on New Year’s Day to a reality directed primarily from parents to children on Christmas Day. , explains Elisa Silva. Guzmán. in her aforementioned article. “Toys, which were one of the many items to be purchased on these dates, became the stars of the show that took place in the windows of foreign trading houses.”

So Christmas moved from chinganas in the streets, to pine trees and old Easters compressed into trinkets and Christmas decorations made in another corner of the world. “In a country where pine was not vernacular and snow was not characteristic of summer except, perhaps, in the mountains or the extreme south of the country, the idea of the Christmas tree was eminently foreign . and incorporated by immigrants – says Godoy -. Its assimilation will only take place during the 20th century, being towards the first decades a custom of foreigners and the economic and social elite which spread to society through advertising in magazines of the time , like Zig-Zag, Sucesos or the press. in general.

Continue reading in Cult

Source: Latercera

I’m Rose Brown , a journalist and writer with over 10 years of experience in the news industry. I specialize in covering tennis-related news for Athletistic, a leading sports media website. My writing is highly regarded for its quick turnaround and accuracy, as well as my ability to tell compelling stories about the sport.